My favourite Git commit

I like Git commit messages. Used well, I think they’re one of the most powerful tools available to document a codebase over its lifetime. I’d like to illustrate that by showing you my favourite ever Git commit.

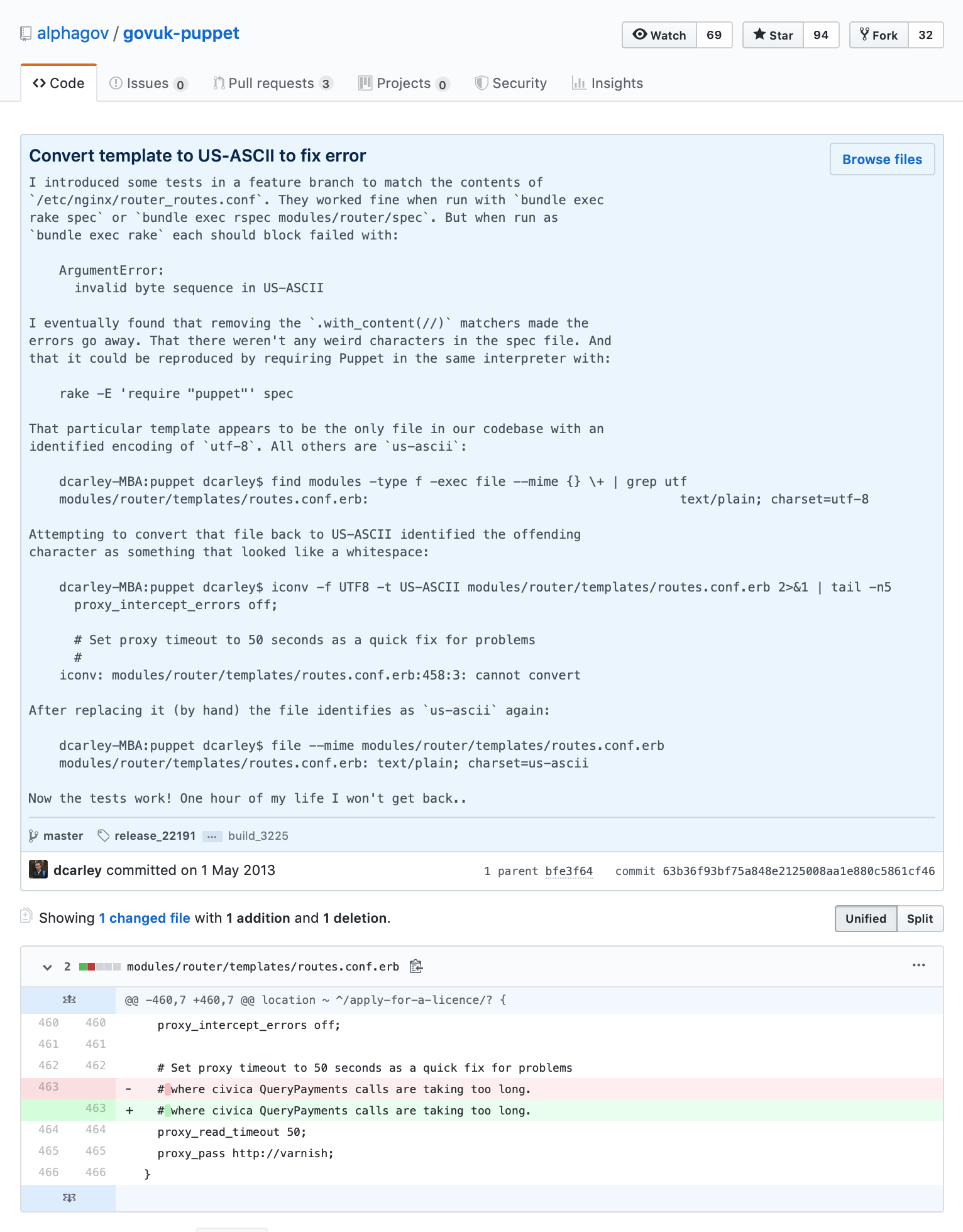

This commit is from my time at the Government Digital Service, working on GOV.UK. It’s from a developer by the name of Dan Carley, and it has the rather unassuming name of “Convert template to US-ASCII to fix error”.

A quick aside: one of the benefits of coding in the open, as practised at GDS, is that it’s possible to share examples like this outside the organisation that produced them. I’m not sure who first introduced that idea to GDS – it was well-established by the time I joined – but I’m forever grateful to them.

Why I like this commit

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve shared this as an example of what commit messages can do. It’s fun because of the ratio of commit message to code change, but that’s not why I think it’s worth sharing.

In a different organisation, from a different developer, this entire commit message might have been change whitespace, or fix bug, or (depending on the team’s culture) some less than flattering opinions about the inventor of the non-breaking space.

Instead, Dan took the time to craft a really useful commit message for the benefit of those around him.

I’d like to step through a few of the ways I think this is a really good example.

It explains the reason for the change

The best commit messages I’ve seen don’t just explain what they’ve changed: they explain why. In this instance:

I introduced some tests in a feature branch to match the contents of

`/etc/nginx/router_routes.conf`. They worked fine when run with `bundle exec

rake spec` or `bundle exec rspec modules/router/spec`. But when run as

`bundle exec rake` each should block failed with:

ArgumentError:

invalid byte sequence in US-ASCII

Without this level of detail, we could hazard a guess that this commit fixed some kind of parsing error in some tool or other. Thanks to the commit message, we know exactly which tool it was.

This kind of information can be really valuable to document, and is all too easy to lose as people forget the original context behind their work, move on to other teams, and eventually leave the organisation.

It’s searchable

One of the first things in this commit message is the error message that inspired the change:

ArgumentError:

invalid byte sequence in US-ASCII

Anyone else who comes across this error can search through the codebase, either

by running git log --grep "invalid byte sequence" or by using GitHub’s commit search.

In fact, from the looks of the search results, multiple people did so, and found out who had found this problem before, when they came across it, and what they did about it.

It tells a story

This commit message goes into a lot of detail about what the problem looked like, what the process of investigating it looked like, and what the process of fixing it looked like. For example:

I eventually found that removing the `.with_content(//)` matchers made the

errors go away. That there weren't any weird characters in the spec file. And

that it could be reproduced by requiring Puppet in the same interpreter

This is one of the areas commit messages can really shine, because they’re documenting the change itself, rather than documenting a particular file, or function, or line of code. This makes them a great place to document this kind of extra information about the journey the codebase has taken.

It makes everyone a little smarter

One thing Dan did here that I really appreciate was to document the commands he ran at each stage. This can be a great lightweight way to spread knowledge around a team. By reading this commit message, someone can learn quite a few useful tips about the Unix toolset:

- they can pass an

-execargument intofindto run a command against each file found - that adding a

\+onto the end of this command does something interesting (it passes many filenames into a singlefilecommand, rather than running the command once per file) file --mimecan tell them the MIME type of a fileiconvexists

The person who reviews this change can learn these things. Anyone who finds this commit later can learn these things. Over enough time and enough commits, this can become a really powerful multiplier for a team.

It builds compassion and trust

Now the tests work! One hour of my life I won't get back..

This last paragraph adds an extra bit of human context. Reading these words, it’s hard not to feel just a little bit of Dan’s frustration at having to spend an hour tracking down a sneaky bug, and satisfaction at fixing it.

Now imagine a similar message attached to a short-term hack, or a piece of prototype code that made its way into production and set down roots (as pieces of prototype code love to do). A commit message like this makes it much easier to remember that every change has a human on the other end of it, making the best decision they could given the information they had at the time.

Good commits matter

I’ll admit this is an extreme example, and I wouldn’t expect all commits (especially ones of this size) to have this level of detail. Still, I think it’s an excellent example of explaining the context behind a change, of helping others to learn, and of contributing to the team’s collective mental model of the codebase.

If you’re interested in learning a bit more about the benefits of good commit messages, and some of the tools that make it easier to structure your changes around them, I can recommend:

- Telling stories through your commits by Joel Chippindale

- A branch in time by Tekin Süleyman